Exactly What You Wanted and Nothing Like You Expected

Syrupy love and other sticky truths

Maria and Lionel at the Enterprise Rent-A-Car on West 83rd know my name by now. This summer, I logged eight 4-plus-hour road trips to the corners of New England for friends’ weddings, family holidays, and my ritual hajj to the ocean for sun, solitude, and realignment. Every time I step into that musty garage, it feels less like paperwork and insurance waivers and more like a portal: swipe your card, choose your spaceship, and suddenly you’re free to cross the threshold of transformation.

I pulled onto the West Side Highway and pointed my grey Nissan Altima toward Brookline for Rosh Hashanah: windows cracked and the Mothership-Sunday-Phish show pouring through the tinny speakers like a syrupy breakfast—sticky, sweet, and a little indulgent—enough of a sugar high to get me to Hartford, at least. It was my last gasp of Indian summer, with Jewish New Year waiting for me just over 200 miles toward the horizon. I packed my suit and headed to Shul for the first of the two high holy days designed for spiritual cleansing and ritual rebirth.

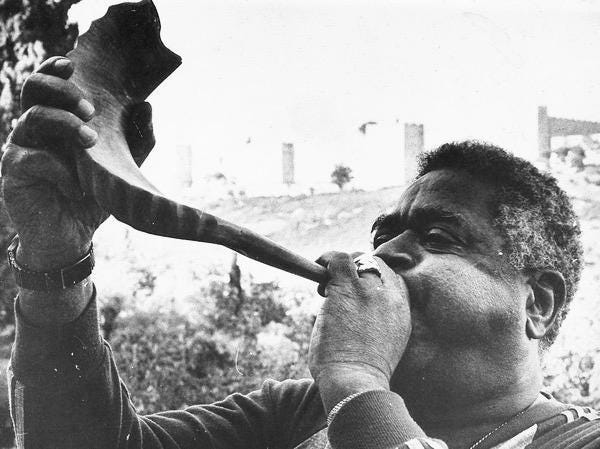

Tuesday morning at synagogue I relished in the blast of the Shofar. For you lovely gentiles, sinners, and Jews who are more Ish, the Shofar is a ceremonial rams-horn-horn that has been announcing the new moon, rallying Maccabees, and startling congregations of bubbes and zaydes for thousands of years.

The shofar has four notes that map the human condition:

Tekiah is presence: the steady note that plants your feet and reminds you to Be Here Now.

Shevarim is fracture: the broken cry that reminds us we’re never whole without breaking first.

Teruah is disruption: the staccato alarm clock that shatters the illusion and demands awakening.

And Tekiah Gedolah is endurance: the long exhale that says: begin again, but this time with more breath, more faith, more heart, more love.

The first tekiah—that long, steady note—cut straight through the chatter in my head. It’s funny how a single sound can do what a thousand thoughts can’t: return you to the room you’re already in. My feet landed on the floor and my Dad leaned in with a cheeky whisper:

“I knew her when she was Abby.”

The program listed the Ba’al Tekiyah (Master of the Blast—best job title ever) as Aviva. The world shifts; identities realign; the sound is the same.

The Rabbi’s sermon that morning was about atonement as a practice. He told the story of Joél, who at 18 took another human’s life and has spent every year since trying to give life back—the first Massachusetts inmate to earn a Boston College degree, now living in perpetual reparation through a dedicated daily practice of social justice.

Rabbi Suzy—sharp, funny, infinite—spoke of going inward to meet the Divine. Their presence itself embodied paradox: masculine and feminine, structure and flow—each word carrying more weight than the one before. In the men’s room, I noticed tampons by the sink, a quiet act of radical hospitality and inclusivity at the edges of being. What better symbol of the Infinite than to carry both?

After temple, in classic Marcus fashion, we rushed out the door to beat the garage traffic, but not before I dropped a few dollars in the Tzedekah box like I had seen my father do the same way for decades. At home, Mom transformed into the Queen of Appetizers: latkes, pigs in a blanket, chopped liver with Tam Tams, apples and honey. A smorgasbord fit for the High Holidays and for her particular love language: feeding people until their chalice overflows.

A beautiful dinner came and went but not before my Aunt Julie caught me in the corner to gush over my writing. It’s a strange bifurcation to share your work online— the phone suggests you’re whispering into the void, while the people who hug you at family dinner tell you they feel seen, moved, and changed.

“Thank you; I receive that,” I replied graciously to her popcorn-string of heart-felt admirations as I embodied my own conscious act of receiving. I’ve been thinking a lot about receivership lately—that learning to hold the gifts of the universe is a skill. No chalice, no wine. And if your chalice leaks? The blessing spills.

As we cleaned up after dinner, I thanked my mom for hosting and repeated something my grandma said that stuck: she didn’t want any birthday gifts, only “time together.” My mom called her mood syrupy—a little too sweet, a little drippy—and I finally understood. Syrupy is what love becomes when it sits out too long: sticky, impossible to ignore, clinging to every surface. The trick isn’t to wipe it away. It’s to find a slice of apple, mop it up, and taste the sweetness.

The last blast at the end of the service is called tekiah gedolah, the great long note. Aviva held it so long her partner looked like she was timing for the Guinness Book of Jewish Records. It’s the exhale that says: Shana Tova. Happy New Year. Begin again, but consciously. It clears your ears so you can finally receive the life you’re already in.

Joél, Rabbi Suzy, Aviva, and me—each of us carried a note within—together comprising the score of the human condition. Joél turned his Shevarim, his fractured cry, into service: a life remade from broken pieces. Rabbi Suzy embodied Tekiah’s steady paradox of infinite presence. Aviva stretched Tekiah Gedolah until the whole room remembered how much breath a soul can hold. And I sat there—startled into attention—feeling the Teruah within, the cosmic alarm clock shattering illusion, waking me up again-and-again-and-again to the beautiful life I’m living.

And maybe that’s the real New Year’s gift: not starting over, but listening more closely to what has been here the whole time and daring to receive it.

Shana tova.

In L.V.X. and Love,

Jonman

Beautiful